Six-year-old Ntokozo has just started his first year of school at Phakamonola Primary School in the Soshanguve Township of South Africa. Like the millions of children who will walk into a classroom for the first time this year, Ntokozo was brimming with anticipation for what it would be like to go to school with all of its new rules, new faces, and new activities.

For many children around the world who come from low-income communities like Ntokozo, going to school requires formidable sacrifices from their families. School is often far from home, supplies and uniforms can be expensive, and children are often needed at home to help support their families. For the parents of these primary schoolers, the sacrifices seem worth it because many know that the power of education can change everything for the next generation.

That’s why perhaps even more heartbreaking than the fact that 58 million children are not attending primary school, is the fact that an additional 250 million are going to school and still not achieving basic literacy skills.

One of the earliest obstacles a child might face is the challenge of trying to learn to read in a language they do not even understand. While it may seem obvious that a child can best learn to read in the language he or she speaks, when it comes to many indigenous languages, this is not always an option. In fact, according to UNESCO more than two billion people lack access to education in their mother tongue.

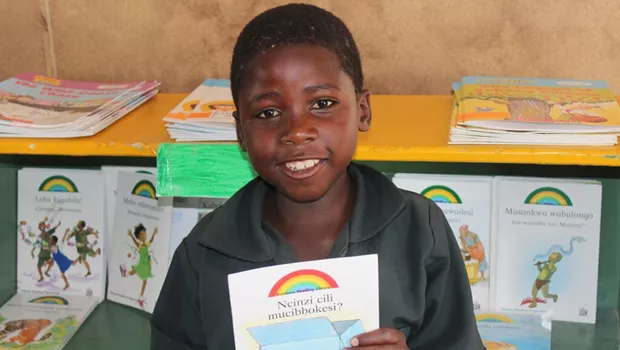

Ntokozo learning in Sepedi at Phakamanola Primary School in South Africa.

Ntokozo speaks Sepedi at home. Spoken by approximately 9% of the South African population, Sepedi is one of the 11 official languages in South Africa. Fortunately for Ntokozo, now Sepedi is one of the home language classes offered for early grade students at his primary school. However, it was only relatively recently that young learners like Ntokozo have had the opportunity to learn to read in their mother tongue.

Imagine all of the uncertainty of your first day of school combined with all of the unfamiliarity of traveling to a place where you don’t speak the language…as a six-year-old like Ntokozo.

As one UNESCO report describes it, “For these learners, school is often an unfamiliar place teaching unfamiliar concepts in an unfamiliar language.” Illustrating this challenge is the story of an educator in a minority language community in India who was attempting to teach in a language the students did not understand.

“The children seemed totally disinterested in the teacher’s monologue. They stared vacantly at the teacher and sometimes at the blackboard where some [letters] had been written. Clearly aware that the children could not understand what he was saying, the teacher proceeded to provide even more detailed explanation in a much louder voice. Later, tired of speaking and realizing that the young children were completely lost, he asked them to start copying the [letters] from the blackboard. ‘My children are very good at copying from the blackboard. By the time they reach Grade 5, they can copy all the answers and memorize them. But only two of the Grade 5 students can actually speak Hindi,’ said the teacher.”

For many of these children, the fact that they are not achieving basic literacy skills has nothing to do with their own innate intelligence or work ethic, and everything to do with the fact that they are expected to build reading skills without the necessary foundation. It is as if they are placed in front of a ladder missing the first several rungs and being told to start climbing.

Willem de Lange for Room to Read.

Willem de Lange for Room to Read.

Research has demonstrated that at the outset of a child’s education the most important skill one can master is not a specific language, but rather reading fluency itself, which is most effectively attained in one’s mother tongue where words and concepts are already linked.

What’s more, long-term studies have demonstrated that those who first achieve fluency in their mother tongue before bridging into a second language consistently perform better in the second language than children who skip directly to the second language.

This is why Room to Read has made foundational reading fluency one of our key success metrics. Room to Read’s Literacy Program helps bridge this gap for students like Ntokozo by developing phonological awareness about word/sound relationships in the oral language with which they are most familiar. When we see our interventions improving reading fluency in the 1st and 2nd grade students we support, we can know that we’re achieving the right results.

Another major challenge facing many minority language speakers is the scarcity of quality reading and instructional materials in those languages.

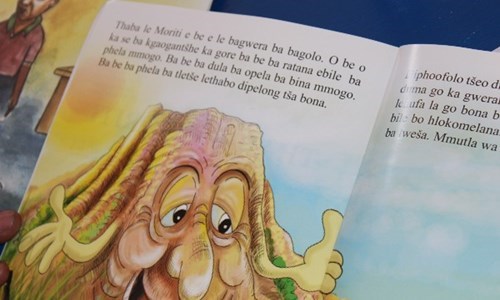

In addition to helping train the teachers at Ntokozo’s school to be more effective in the classroom, Room to Read also develops and supplies research-based instructional materials in local languages. Room to Read continues to support the development of literacy by establishing libraries that are filled with local-language reading materials, often published by Room to Read — books like “The Mountain and His Shadow,” a Sepedi book that Ntokozo can find in the library Room to Read established at his school.

Designed for early readers, the book has colorful illustrations of a mountain that looks just like the mountains Ntokozo might see outside his window. Having regular access to and practice with engaging, culturally-representative material in their own language helps motivate students to practice and improve their literacy skills and build a habit of reading that will put them on a path for lifelong learning. Room to Read’s education specialists take great pains to understand this process and design effective programs so that young students like Ntokozo don’t have to take great pains to learn how to read.

Back in Ntokozo’s classroom, all the students are filled with excitement and seem comfortable in their environment. Holding a book in one hand and a pen in the other, Ntokozo’s teacher, Margaret, asks the little ones how many items she is holding. In just his third week of school Ntokozo is unselfconsciously shouting out the answers without following the class rules to put up his hand before blurting out the answer. “Pedi” he shouts, which means “two” in Sepedi — the language he doesn’t have to struggle to learn because it’s what he speaks at home.

When these young students can learn in their mother tongue, they can not only get on the ladder to literacy, they can climb it faster than a jungle gym.

Learn more about Room to Read’s Literacy Program and work in South Africa.